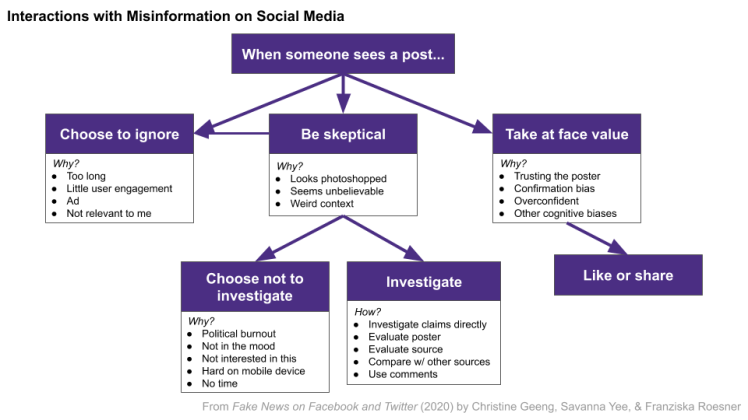

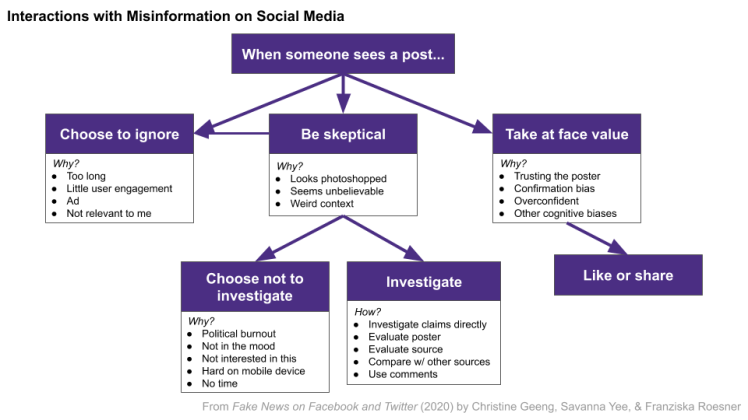

It’s been a long hot mess of a summer but I’m finally sitting down to write a summary of my CHI 2020 paper Fake News on Facebook and Twitter to try to make my paper contents more digestible. And also my rad advisor Franzi created this amazing flow chart after it had been published, but I want this to live on.

Look at those beautiful purple arrows.

Research Questions

Misinformation has become a huge societal issue, as viral falsehoods spread on social media which affect issues ranging from elections to public health. One important aspect of studying misinformation, in addition to studying how it spreads and who spreads it, is understanding how people interact with it when it shows up on their social media feed.

Our research questions were:

- How do people interact with misinformation posts on their social media feeds (particularly, Facebook and Twitter)?

- How do people investigate whether a post is accurate?

- When people fail to investigate a false post, what are the reasons for this?

- When people do investigate a post, what are the platform affordances they use, and what are the ad-hoc strategies they use that could inspire future affordances?

Methods

Previous research had study participants look at misinformation on social media through someone they don’t know or they’ve been asked to follow by the researcher. We wanted to observe how participants interact with misinformation posted by people they know.

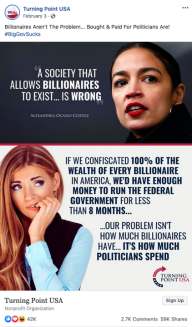

To do so, we developed a browser extension that changed the appearance of participants’ Facebook or Twitter feeds (without them knowing) to seem as if misinformation posts we chose was posted by accounts on a participant’s feed. (Participants could not share misinformation online or offline, and were explained the true nature of the extension at the end of the study). These debunked misinformation posts were selected from Snopes.

An example Snopes-debunked Facebook post that would show up on a participant's feed, with the poster of this content replaced by a poster on their feed. (Turning Point is a right-wing organization with low factual reporting.)

We recruited 25 people who use Facebook or Twitter daily or weekly for various news. They were first interviewed about their general social media use, then were instructed to scroll through their modified feed while thinking aloud (on laptops), and then finally asked questions about their experiences with misinformation, before being debriefed about the extension and the misinformation posts that showed up on their feed.

Results

We observed a variety of interactions with misinformation, ranging from ignoring a post, being skeptical of it, to taking it at face value. When a participant was skeptical, some would investigate more deeply into its content and others chose to scroll past it.

We found that, for participants who investigated posts, they tended to use platform affordances whose primary functionalities aren’t related to fact-checking or adding context to news. Some participants said they looked at comments to see if anyone already called it false, or we observed them looking at poster bios for more context. None of our participants used or had heard of the Facebook “i” button, which shows contextual information about article source websites, such as date created.

Takeaways

Determining Credibility

Many of our participants examined how much they trusted the poster in order to determine post credibility, which a previous study has shown is a heuristic people relied on more than an article source when they had low motivation or interest in an article. Other credibility heuristics that participants used (other than poster trust and source reputation) included consistency of information with other sources, expectancy violation (if a poster didn’t normally post such content), and determining if content was an ad.

Lessons for Designers

Make falsehood labels big! Users have a hard time noticing small affordances (such as the “i” button). Facebook and Twitter have both since rolled out more visible labels for manipulated media and debunked content.

Lessons for Us as Information Consumers

Combatting dis/misinformation is a platform responsibility (as social media companies are the institutions with money and power), but there are things we can look out for as individuals to also be more responsible information consumers.

While several participants mentioned they were news skeptics or hadn’t been fooled by misinformation before, during our study there were moments where they took content at face value. This shows that even when we value the facts, casual media consumption can inadvertently lead to believing falsehoods. We recommend ignoring headlines unless one is going to take the time to read the article content and check out its source.

Future Research Questions

Misinformation interactions is affected by the medium of the content (whether its longform or a short meme), as well as how motivated people are in the content. Future work should investigate how much (or little) people may focus on article content versus images or memes when scrolling through social media on phones.